In the Jomon Period (10,000-300 BCE), people lived in pit houses. In the following Yayoi Period (300 BCE-300 CE) new cultural influences arrived from Korea to introduce wet rice agriculture, which required storing grain in raised structures to protect them from water and rats.

In following periods, farmhouses adopted both practices. The kitchen and other work areas were situated on a packed dirt floor, whereas the living room and other peripheral rooms were constructed on a raised floor. The basic structure was post and beam with a large thatched roof. After the introduction of continental influence in the 6th century, thatch was often replaced with tiles.

There is a great deal of variation in farmhouses (minka) in Japan. Gassho style farmhouses have steep roofs suitable for areas with snow; magariya are L-shape houses of northeastern Japan that include a living space for the family as well as a stable for animals. Another northern style is the Kabutoyana (samurai helmet) roof that allows windows on the upper floors, an important consideration in the winter when windows on the ground floor are covered with snow.

On the southern island of Kyushu, U-shaped Kudo style houses were constructed "back to the wind" to withstand typhoons. There are many other basic shapes and roof ridge styles found in rural areas.

In general, farmhouses were large enough to accommodate multiple generations --in some cases as much as thirty people or more. With their high ceilings and uninsulated walls, they were crafty and difficult to heat in the winter. Some farmhouses had an open hearth in the main living area, around which family members would sit for tea in the evenings. The interior space could be divided into smaller areas by sliding doors.

Urban merchant houses known as machiya were similar in construction with both a raised living area and a working area on a dirt floor. Machiya were long homes with narrow street frontage, usually containing one or more courtyard gardens. Two or three stories high, the front of the house served as retail space, with the back providing living space.

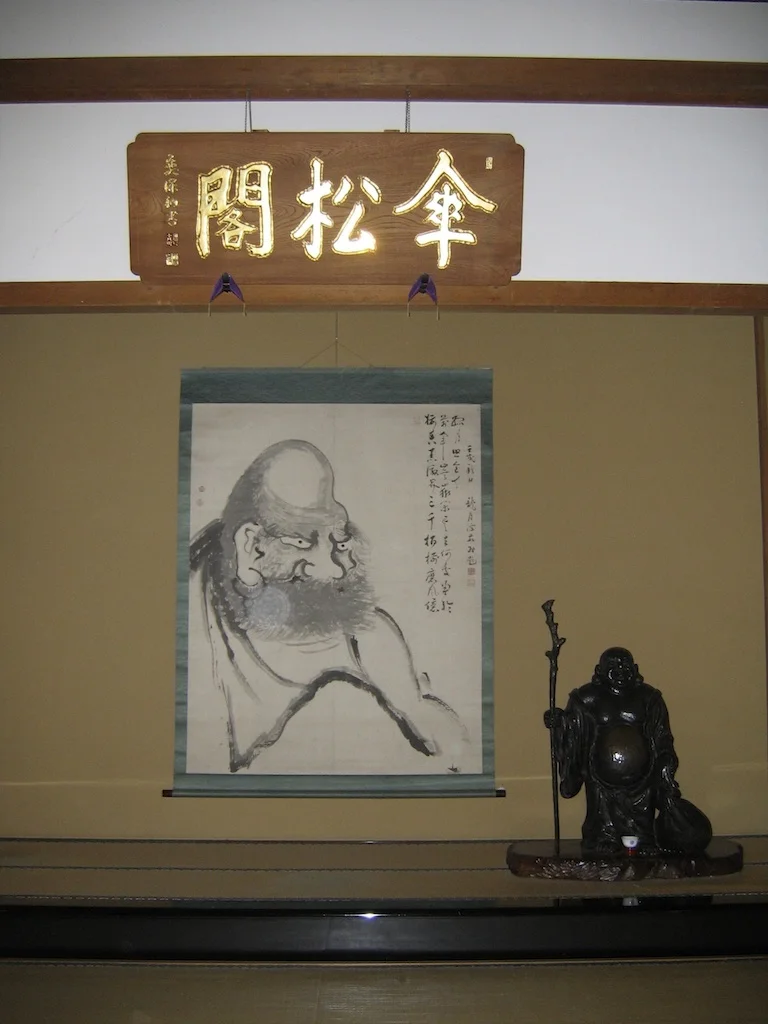

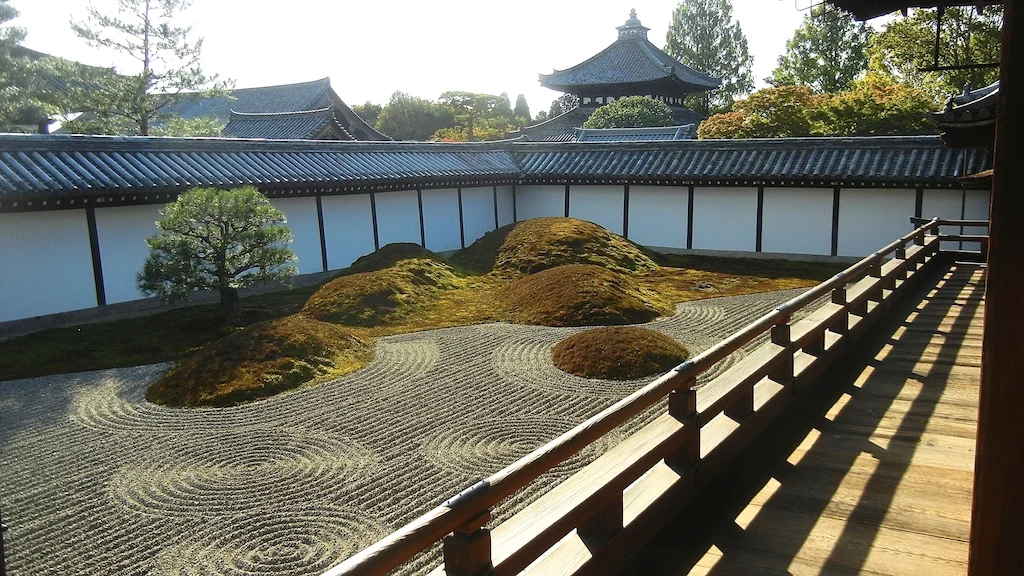

In many cases, traditional houses, particularly in urban areas, consisted of rooms that look over a long deck that runs partway around the house. One steps from the tatami mats on the interior of the house to the wooden deck, and then down into the garden. The deck is separated from the garden by sliding doors: wood, glass, screen, and paper, that can be opened and closed depending upon the weather. Sometimes, a toilet is situated at one end of the deck and the bath is situated at the other end --keeping the two opposite bodily functions as far apart as possible. Important rooms have recessed alcoves (tokonoma) for displaying art objects.

Traditional inns are similar in structure, with a reception area, tatami mat guest rooms, bath and toilet areas, kitchen and a garden. Traditionally, meals are served in the guest rooms on low tables. After dinner, the table is moved to one side and bedding is removed from closets and laid out on the tatami mats. The bath usually consists of separate areas for males and females and may have only small wood or ceramic tubs where one soaks after washing thoroughly outside the tub. The hot water in some inns is supplied by natural hot springs, in which case the bathing area may consist of both large indoor and outdoor pools.

Traditional homes and inns have a foyer (genkan) where shoes are left before stepping up onto the tatami mat area. There are separate slippers for wooden decks, toilets, bath, and garden.

Today, traditional domestic architecture is often replaced with Western style wood frame structures with insulated walls. Such buildings are less costly to build and easier to heat. Unlike traditional houses that had very little furniture, modern Western style homes employ Western style furniture such as tables, chairs, and beds.